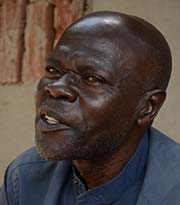

Fred Matalocu

Fred Matalocu, a 65-year-old Ugandan, remembers when his community was devastated by a disease that caused intense itching. So intense, in fact, that people scratching themselves with their fingernails was “insufficient” at getting relief. People sometimes turned to using rocks and sticks to ease the pain. Skin damage and vision loss followed later, all caused by river blindness, a parasitic disease spread by the bites of tiny black flies.

Matalocu’s community of Moyo district lies at Uganda’s border with South Sudan, 280 miles (455 kilometers) from Uganda’s capital, Kampala. The Albert Nile River flows north and east through Moyo before turning north again and joining the White Nile in South Sudan. The rapidly flowing tributaries of the Nile make ideal breeding grounds for the black flies that transmit river blindness.

According to Matalocu, the people of Moyo began avoiding farming near the rivers and nearby small streams to avoid the effects of the disease.

The tide began to change in 1993, when The Carter Center and Uganda’s Ministry of Health commenced activities in Moyo to control the disease with drug treatment and health education. And in 2007, Uganda shifted its river blindness program from mere control to elimination, which calls for more frequent drug treatment. Significant progress has followed.

After 28 years of treatments with Mectizan® (donated by Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, New Jersey), the entire Madi-Mid North area, which includes Moyo, has reached a stage where experts suspect that transmission of river blindness is interrupted, a major step toward eventual elimination. For now, transmission interruption must be confirmed in various ways, such as the testing of black flies. Later, drug treatment will be halted followed by at least three years of post-treatment surveillance.

The decline of river blindness has changed everything, Matalocu said. Crops can be planted near the fast-flowing rivers and streams now; people are healthier and more productive; children can go to school instead of staying home to help blinded family members.

He appreciates what the program has meant for him, his family, and his community: “Because of the treatment, our grandchildren will have a better future,” he said.

Learn more about the Center's River Blindness Elimination Program »

Please sign up below for important news about the work of The Carter Center and special event invitations.