Carter Center Malaria Control Program Assistant Director Amy Patterson reflects in the blog below on the challenges and opportunities for increasing the use of bed nets in communities in Nigeria.

At the invitation of the Nigerian government, The Carter Center began health program work in Nigeria in 1988. In 2010, the largest long-lasting insecticidal net distribution effort in history to fight malaria was launched in Nigeria, which bears more deaths from this disease than any other country. The goal is to provide every household in the country with two nets. The Carter Center is a part of this epic activity, focusing efforts on the nine states where we have supported other neglected disease control and elimination programs including lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, schistosomiasis, and trachoma. Learn more about the Carter Center’s Malaria Control Program>

During a recent field visit to Nigeria, I visited some villages in Plateau State with several members of our Nigeria office to talk to people about the things that make it hard to use bed nets as well as the things that encourage use. The purpose of these conversations was to get ideas about what else we might be able to do to increase the use of the more than1.4 million long-lasting insecticidal bed nets that The Carter Center has helped to distribute in the state, in partnership with the Federal Ministry of Health. In particular, we wanted to get ideas about the kinds of messages we should emphasize in our health education and communication activities–a project that I have been working on with Adamu Sallau, director of the Carter Center’s malaria program in Nigeria. We hope communicating these additional messages will result in behavioral change.

Often, just telling people that malaria is a dangerous disease, that it is transmitted by mosquitoes, and that it can be prevented by sleeping under a net is not enough to bring about behavior change. Some people aren’t motivated by that argument, but could be persuaded by different messages. Others might really want to use nets but are prevented from doing so by things like lack of access to a net, lack of empowerment to make decisions in their household, or lack of the skills to hang and use a net properly in the place where they usually sleep.

When trying to help people to understand this, Adamu likes to use the example of exercise: How many of us know that exercise is good for our health? And yet how many still don’t exercise regularly? What are the things that keep us from exercising even when we know it’s important?

When we talked with villagers in Plateau State, people mentioned numerous things that make it hard to use nets. Many were the ‘usual suspects,’ such as finding nets too hot to sleep under or worrying about the safety of insecticides. However, they also said many things I hadn’t heard before.

For example, young boys said they got home when it already was too dark to see well enough to pull down the sides of their nets to tuck them in (especially when they don’t have electricity in their house, or due to the frequent power outages). They said using a net wasn’t “cool” and that young men often think they are invincible, or that they are protected from malaria by drinking beer.

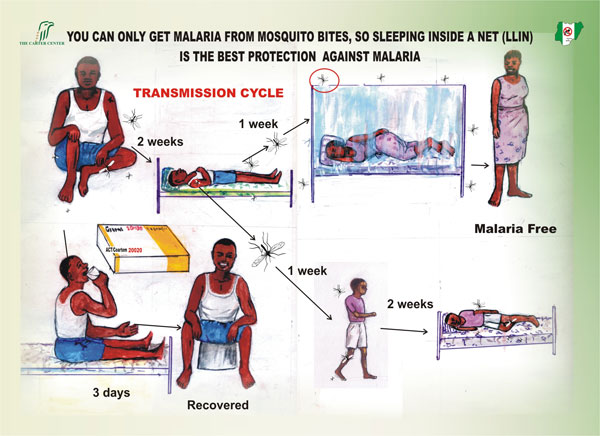

This page from a health education flip chart shows people that they can prevent malaria by sleeping under a long-lasting insecticidal bed net. Recent focus group discussions are helping to inform revisions and improvements to these flip charts, so community volunteers can use them during house-to-house behavior change activities.

Some young women said they had trouble convincing their husbands to use nets and thus were not able to use them. Many people said that they didn’t know how to hang a net if they sleep on a mat instead of a bed, or when they sleep outside, as is common during the hot season. Others said the shape and size of the nets makes them hard to hang in the small rooms that students and young couples often rent in peri-urban neighborhoods. These are all things that The Carter Center can find ways to address.

People also talked about what motivates them–or would make it easier–to use nets, many of which were not directly related to malaria. Young women said that nets are “fashionable,” and that using a net keeps their skin beautiful by protecting them from mosquito bites.

Men and boys were particularly motivated to use nets when they learned that nets could protect them from the swollen genitals and legs that commonly result from lymphatic filariasis. As one boy said, “Now that I know that, I will definitely start using my net. You should tell everyone that!”

Carter Center Malaria Control Program Assistant Director Amy Patterson (above) in Nigeria earlier this summer, evaluates how freely provided bed nets are being used. Since 2004, The Carter Center, in partnership with the Nigerian government and endemic communities, has supported the distribution of more than 4 million bed nets in areas where the Center works. In 2012, the Center expects to assist with the distribution of at least 4.6 million more.

People said peer pressure and reminders from family members encourage them to use nets, and that it was easier for men and boys who come home late to use a net if another family member already had hung it and tucked in the sides for them. Emphasizing some of these other benefits and strategies in the Carter Center’s communications can persuade even more people to use nets.

Adamu and the other members of the Nigeria team are passionately committed to the project of increasing net use to prevent more of the millions of potentially fatal cases of malaria that Nigerians suffer from each year. In the coming months, they will be training community volunteers to address various barriers to using nets during house-to-house visits in Plateau.

These volunteers are trusted and reliable people, selected by the communities they serve. They already work with The Carter Center to deliver treatments for other diseases at the household and community levels, dedicating their time, without pay, to improve directly the lives of their neighbors and indirectly contribute to the economic health of their entire country by reducing school and work absences.

I am incredibly impressed by–and grateful to–these volunteers as well as to our extremely dedicated Nigerian staff who constantly work to expand and improve the Center’s work to control malaria in Nigeria.

Please sign up below for important news about the work of The Carter Center and special event invitations.